India has made impressive progress in rural electrification (RE) since the government of India shifted its policy focus towards universal household electrification since early 2000s. However, evidence suggests limited impacts on household incomes and expenditures since agriculture still drives the economy and electricity is primarily used for generating income through pumping groundwater for irrigation - one of the important factors affecting prosperity among small holder farmers informs this paper titled 'The changing impact of rural electrification on Indian agriculture' published in Nature Communications.

To make India self sufficient in grain production, it was realised that reliable and steady sources of irrigation were necessary for the success of the Green Revolution (GR). Regions that enjoyed GR-led increases in agricultural production had highly politicised agrarian lobbies who demanded better and cheaper resources to increase agricultural production.

Thus, agricultural electricity coverage was increased in these states and electricity rates were also subsidised. Electricity for agricultural use was given more importance as compared to household electrification. By the early 1990s, the focus on grain production was reduced and thus rural electrification (RE) lagged behind in states which had lost out on GR-driven demand for electricity.

The second wave of RE focused on domestic electrification in the early 2000s. The Rajiv Gandhi Grameen Vidyutikaran Yojana (RGGVY) launched in 2005, provided 90 percent grant-based financing to states for universal household electrification and free electricity connections for households below the poverty line.

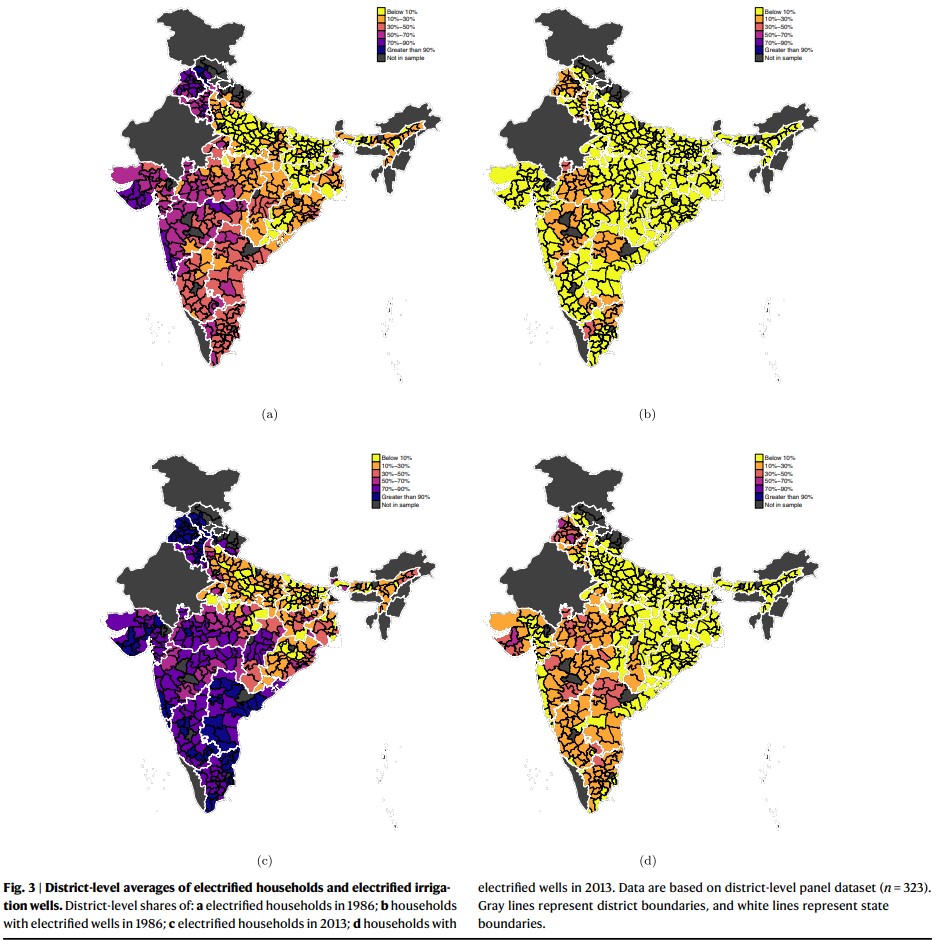

States were granted funding by the central government based on the number of rural households that needed electricity connections and prescribed electricity loads per household. Thus while RGGVY has led to rapid expansion of RE in India, but while it has been relatively successful in bridging the regional gap in household electrification, large regional differences still remain in electrified pumping of groundwater.

The latest government numbers indicate near universal household electrification. However, very little information is available on the short-term or long-term impacts of RGGVY on rural economy and agriculture in India.

This paper discusses the findings of a study that examines the consequences of this imbalance in rural electrification policy on agricultural development in India.

Agriculture and groundwater irrigation in India

Agriculture employs over 70 percent of the country’s rural working population and a large majority of small holder farmers depend on irrigation through pumping of groundwater because of its relatively low variable cost of extraction (provided the presence of electricity infrastructure) and individual accessibility.

Groundwater can be accessed during dry cultivation months (the Rabi season) when surface water flow is diminished, making it an effective source of irrigation. Additionally, wells also give farmers independence, as it relieves them from the competing uses of hydropower generation and riparian rights like canals.

Groundwater extraction in India has been increasing with increase in the number of deep tube-wells with depths greater than 70m, which require submersible pump-sets that run on electricity. Even shallow wells now use electricity for pumping as diesel is now more expensive than agricultural electricity in most Indian states. Hence it is used alone or in combination only in cases where electricity is unavailable or is intermittent or suffers from low voltage.

Where available, electricity is subsidised by way of flat or no tariffs reducing the marginal cost of consuming electricity and cheap electricity to agriculture has given rise to a strong groundwater-electricity nexus that is difficult to break due to political and electoral considerations, and led to further depletion of groundwater resources. Government procurement of rice and wheat also creates strong incentives to grow water-intensive crops further affecting groundwater depletion rates.

Limited groundwater irrigation in groundwater rich areas: The paradox

However, there are parts of India where groundwater levels are healthy, but limited groundwater irrigation puts limitations on dry season cultivation and these districts see a much smaller share of cultivated area under irrigation. A high water deficit during the winter dry season adds to the low levels of winter cultivation.

This variation in groundwater irrigation does not have anything to do with its availability, but it has to do with the unavailability of electricity needed to pump groundwater. Poor access to electricity limits groundwater irrigation in groundwater abundant regions of India.

The study

The study distinguishes between districts that were electrified during irrigation-focused RE policy during the green revolution from districts that were electrified post a shift towards domestic consumption. It refers to them as non policy change (non-PC) districts for the first category and policy change (PC) districts for the latter.

The study finds that:

Household electrification has few spillovers to agricultural electricity after policy change

There are similar differences between policy change (PC) and non policy change (non-PC) districts for areas irrigated by groundwater wells across cropping seasons - Kharif during monsoons and Rabi during dry winter. While groundwater irrigation is particularly relevant during Rabi, changing rainfall patterns have made groundwater irrigation important even during Kharif in recent years.

The study finds an increase in irrigated area across all seasons among non-PC districts on average, but a large penalty associated with electrification post policy change. Particularly for Rabi, the negative penalty of electrification post policy change is so large that there are no increases in irrigated area associated with household electrification among PC districts.

Income does not explain irrigation differences between PC and non-PC districts

RGGVY removed the costs of domestic connections for households below the poverty line, which led to increase in the rates of domestic electrification, but no increase was found in electricity connections for groundwater irrigation.

Transformer size in RGGVY is based on aggregation of the number of households to be electrified and load capacity per household. The highest prescribed load capacity of a single household at 500 W is incapable of running even a 1 HP electric pump and majority of the wells and deep tube-wells were operated with pumps of capacities below 2 HP in 2013. Deep tube-wells have depths greater than 70 m and require pumps with capacities greater than 10 HP. Therefore, in PC districts where electrification majorly occurred under the RGGVY program, transformer capacities constrain households with the financial means to access electricity for groundwater irrigation.

Compared to the poorest 15th percentile of households, all other farming households in non-PC districts irrigated larger amounts of cultivated land during Rabi. However, no similar difference in irrigated area was found between the poorest 15th percentile households in non-PC districts and households among PC districts that were even in the top 85th consumption percentile. No wealth gradient was detected for Kharif irrigated area as monsoons decrease the demand for groundwater irrigation during Kharif.

Poor physical access to electricity in terms of duration of supply, voltage fluctuations, brownouts, and blackouts, transformer failure and limited transformer capacities are major factors preventing farmers from using electricity for pumping groundwater for irrigation.

Use of electricity for groundwater irrigation shows regional differences

Despite the ubiquitous presence of electricity infrastructure across rural India, the use of electricity for groundwater irrigation remains regionally concentrated. Large parts of regions electrified post policy change are located in eastern India with healthy groundwater levels, low cropping intensities, and lower irrigation requirements and have the potential to become the future bread basket of the country. However, cultivation expansion in the east is unlikely to occur with current levels of irrigation.

Thus, increasing Rabi cultivation in the east by fixing the electricity infrastructure to serve groundwater irrigation can help safeguard India’s future food security while preventing overexploitation of groundwater in groundwater depleted areas. However, only providing irrigation access in PC areas will need to be complemented by well-functioning agricultural markets and policy interventions as government procurement dominates the Indian agricultural markets, argues the paper.