- Topics

- Feature

- Opportunities & Events

- About

- Hindi Portal

- Data

- Topics

- Feature

- Opportunities & Events

- About

- Hindi Portal

- Data

Drought is one of the most damaging natural hazards India faces. It does not arrive suddenly like a flood or a cyclone. Instead, it builds quietly when rainfall remains below normal for long periods, slowly tightening water availability. When this happens, food production suffers, health risks increase, and local economies weaken.

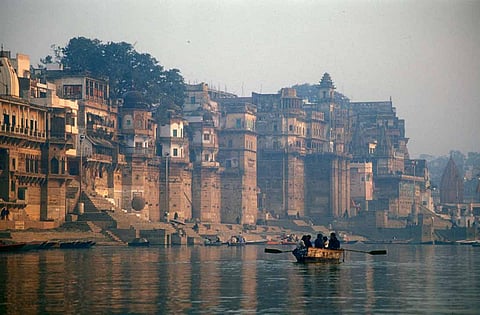

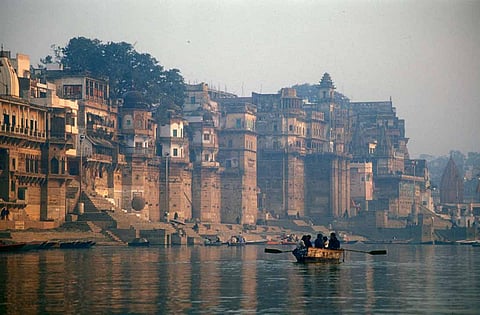

In India, where most farming depends on the monsoon, droughts place millions of livelihoods at risk. Their impacts are felt most sharply in already vulnerable regions, deepening inequality and distress. A new study now warns that drought conditions are intensifying in the Ganga River Basin, often called the lifeline of India because it supports agriculture, water needs, and livelihoods for millions.

The Ganga River Basin spans about 1.086 million square kilometres, covering five states in northern India and extending into Nepal, Bangladesh, and China. It includes major cities such as New Delhi, Kanpur, Lucknow, Varanasi, Prayagraj, Patna, and Kolkata. More than 500 million people depend on this basin for water, food, and income. It also supports diverse ecosystems and a wide range of farming systems.

Over the past few decades, rainfall patterns across the basin have changed noticeably. These shifts have made rural communities, especially those dependent on agriculture and natural water flows, increasingly vulnerable. Reports of crop failures, falling water availability, and disrupted livelihoods linked to drought are common. However, studies that bring together multiple drought indicators to understand these changes across the entire basin have been limited.

The study, titled Drought risk and hydrological changes in the Ganga River Basin, India’ from Physics and Chemistry of the Earth, published in Physics and Chemistry of the Earth, addresses this gap. It analyses long-term trends in rainfall, temperature, and evapotranspiration across the basin from 1980 to 2020.

To assess drought conditions more comprehensively, the researchers used multiple indicators. These include the Standardised Precipitation Index (SPI), which captures short-term and long-term rainfall anomalies; the Streamflow Drought Index (SDI), which measures water availability based on river flows; and the Evaporative Stress Index (ESI), which helps detect early vegetation stress caused by imbalances between actual and potential evapotranspiration.

Together, these indicators offer a clearer picture of how drought risk and hydrological changes are unfolding across the Ganga Basin, with serious implications for water security, agriculture, and livelihoods.

Uttar Pradesh, Bihar and Jharkhand show the maximum decline in rainfall

Rainfall is steadily declining across key parts of the Ganga Basin. The most affected areas include Eastern Uttar Pradesh, Bihar, Jharkhand, Northern Madhya Pradesh and Chhattisgarh fringes. Both yearly and monsoon season trends show a clear drop in rainfall, especially in the central plains and eastern humid zones.

This is a matter of great concern, as these regions are vital for crop production. Less rain means weaker groundwater recharge, and ecosystems that depend on seasonal rains are under stress. This contraction of monsoonal rainfall threatens the resilience of one of India’s most important agricultural zones.

Number of rainy days across the basin have declined

The number of rainy days is going down across the Ganga River Basin—especially in eastern Uttar Pradesh, central Bihar, northern Jharkhand, and parts of Madhya Pradesh and Chhattisgarh. The rain is coming in fewer, heavier bursts; dry spells are getting longer, and wet seasons are getting shorter. These changes will affect farmers who rely on rain, groundwater recharge and the overall water balance in the region. In an area that is already facing droughts, this shift makes things even harder.

Lighter rains have disappeared too

There has been a drop not just in heavy rains but also in lighter rainfall events across the central-eastern Ganga River Basin across Northern Madhya Pradesh, Bihar and Eastern Uttar Pradesh. Lesser light rainfall events can mean lesser availability of soil moisture during dry spells, lower chances for groundwater recharge and bigger negative impacts on farming and water security. Small showers play a big role in keeping the land hydrated. Their decline signals deeper shifts in the monsoon—and bigger risks for the region.

The basin is seeing a new monsoon divide with scanty to heavy rainfall events

Rainfall is being rewritten across the Ganga Basin. Regions in the Central and Southern Basin, such as Madhya Pradesh, Chhattisgarh, and parts of Bihar, are seeing a steady decline in light to moderate rainfall. This means less soil moisture, lower groundwater recharge and longer dry spells.

At the same time, more extreme rainfall events are rising in the North and South-west, such as in the Uttarakhand and Nepal border zones and Southeastern Rajasthan and western Madhya Pradesh. These areas face growing risks of flash floods, landslides and water management challenges.

The basin is experiencing a redistribution of rainfall intensity, with serious implications for flood preparedness, water resource planning and agricultural resilience

Temperature trends show that the Basin is warming rapidly

Warming is happening in all seasons but varies by region. For example, Eastern areas like Bihar and Jharkhand and southern parts of the basin are warming during the post-monsoon season. Southern and southeastern regions, including the Chotanagpur plateau, show warming during the winter. Central UP, northern MP, and northern Bihar heat up before the monsoon and warming continues, especially in central and eastern parts, even during the monsoon.

Cold extremes are fading

Cold nights are decreasing in the central and southern basin. Extreme nighttime cold is declining even in the Himalayan foothills, including high-altitude zones. Cold days are becoming less frequent across the Indo-Gangetic plains and western semi-arid regions. Warm nighttime temperatures are increasing basin-wide. The most pronounced warming is seen in the eastern, central, and southeastern regions. This pattern points to a basin-wide reduction in cold extremes and a rise in warm extremes, even in climate-sensitive Himalayan zones.

These can alter crop cycles and heat stress thresholds, affect water demand, evaporation, and ecosystem health, and threaten fragile mountain habitats and snow-dependent systems

Fluctuating temperatures are increasing the risk to agricultural and water cycles.

Daily fluctuations between highest and lowest temperatures are increasing, and these can stress crops, impact evaporation rates and soil moisture and dew formation and affect water cycles while increasing climate change impacts and heating.

Seasonally, the pre-monsoon and post-monsoon periods are warming the fastest, highlighting critical transitional windows that can significantly influence hydrological and agricultural cycles in the Ganga River Basin.

Evapotranspiration is rising

Evapotranspiration (ET) is the process by which water moves from land to air through evaporation and plant transpiration. It’s a key part of the water cycle—and it’s changing across the Ganga Basin by seasons.

ET is increasing in Bihar, West Bengal, and southern parts of the basin (up to +2 mm/year) during the premonsoon season and is also high during the monsoon, with further increases in northern Bihar. the Terai, and central Uttar Pradesh. Yearly trends show that ET is rising in the Himalayan region and southeastern parts of the basin—up to +5 mm/year. I

Rising ET can affect water balance and availability, crop water needs and irrigation planning and ecosystem health, especially in sensitive zones. These shifts are being driven by rising temperatures and changing rainfall patterns, signaling a warmer and more water-stressed future.

Evaporative Stress Index is rising

The Evaporative Stress Index (ESI) shows how stressed the land is from losing moisture, and a higher ESI means more stress. Even with rain, high temperatures are causing high stress across the basin during the post-monsoon season. Yearly trends show that there is moderate stress across the basin, and the northern and central regions show the most stress.

Standard Precipitation Index shows drier conditions

The Standard Precipitation Index (SPI) shows how wet or dry it is, and negative SPI values show drier conditions. The Ganga River Basin is getting drier, especially in September.

Short-term estimates also show that drying increases in August and September, especially in the east and Himalayan foothills. Long-term estimates show strong drying across central, eastern, and northern areas with a rising risk of long-lasting droughts.

This shows that there will be less rain recharge during the monsoon; higher temperatures and moisture loss make dryness worse, and even mountain areas are starting to feel the stress.

Streamflow drought index shows increasing dry spells

From June to September, streamflow droughts are becoming more frequent and severe across the Ganga River Basin. Scientists used the Streamflow Drought Index (SDI) to track these changes over time.

Short-term drought trends show that areas like southeastern Uttar Pradesh and northern Jharkhand are seeing more frequent dry spells in July and August. Long-term drought trends show that 60–70% of the basin shows strong drying by September, especially in southern UP, central Bihar, and northern Madhya Pradesh. This suggests less water in rivers, even during the monsoon, and is linked to changing rainfall patterns and land use.

The findings show that water stress in the basin is intensifying due to declining rainfall, increasing temperatures, and rising atmospheric demand. To address these emerging challenges, region-specific adaptive water management strategies must be implemented. These can include integrated watershed management to enhance natural recharge, promotion of rainwater harvesting and managed aquifer recharge, crop diversification towards water-efficient varieties, and expansion of micro-irrigation systems.

Development of a robust drought early warning system and the integration of climate trends into water allocation policies will also be crucial to support long-term water and food security in the Ganga River Basin.