This bilingual book written in Hindi and English appearing side-by-side titled “Bagawat par majboor Mithila ki Kamla nadi” and “Kamla: River and the people on collision course” respectively attempts to study the irrigation and flood control schemes that were taken up in the Kamla basin following independence and depicts how people have been left in a blind alley.

The Kamla is a very holy river of Mithila, the land of Janak, Sita, Ashtavakra, Yagyavalka, Vachaspati Mishra and Vidyapati. Mithila region and the river Kamla remain in news for very different reasons these days. It is the flood capital of the country and the Kamla occupies an important place on the flood map of India. This book is an attempt to highlight this facet of the river.

The river originates from the Mahabharat range in the Himalayas in Nepal and enters India in the Madhubani district. This river joins the Balan and the resulting stream is called the Kamla-Balan. There was a very severe flood in Bihar, in the year 1954 when the Kamla turned eastwards and joined the course of the Balan near Pipra Ghat. The changing courses of almost all the rivers along with the embankments built on the rivers to prevent this shift have changed the entire drainage mechanism of the area.

The Kamla changes its course from time to time and many of its abandoned channels become active during the rainy season and can be seen on the western side of the present stream of the Kamla-Balan. Four different channels of the rivers are known to have existed – Bacchiraja Dhar, Pat Ghat Kamla, Sakri Kamla and Jiwach Kamla. In the lower reaches, the Kamla-Balan bifurcates near the village Gulma.

The author Dinesh Kumar Mishra notes that the “Kamla river in the Mithila region of Bihar is not associated with the harrowing tales of destruction that are associated with rivers like Kosi. The waters of the river are known to carry far more nutrients and the basin is considered to be more productive [about 80 kg of paddy per 1 kattha (3 decimals) of land]. The river is popular in the folk tales and legends but not in Hindu scriptures or Jain or Buddhist literature.”

The floods of the Kamla and the Balan used to reach up to the Deep village, west of Tamuria while on the right bank, its spread extended up to the Pat Ghat Kamla. A major portion of the Kamla in the Indian territory now lies in the Madhubani district that earlier used to be a sub-division of what was earlier Darbhanga. Old British records reveal that irrigation was neither needed nor practiced in Darbhanga and the Samastipur sub-division of Darbhanga.

The small rivers originating in Nepal, acquire a big shape when they enter Madhubani and it was generally not possible for the farmers and the zamindars (landlords) to tamper with these rivers. Also, the spread of the floodwater was so vast and wide that only the requirement of the monsoon paddy was met with. The moisture retained in the soil was enough to meet the needs of the rabi crops also. The extent, duration and the depth of the floods were generally, known to everybody and the farmers had with them the varieties of paddy seeds to suit every given condition.

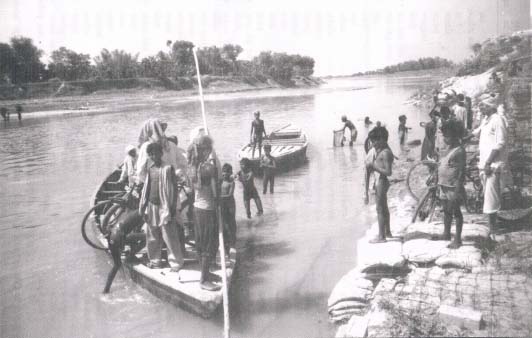

Image courtesy: Dinesh Mishra

The situation in Madhubani was a bit different and irrigation was needed there in the rabi season and, it is for this reason, there existed a very efficient and well thought out irrigation system with the help of pynes and tanks. There are people who still survive to tell about the indigenous system of irrigation but the wisdom is dying slowly and within years all these people will be no more with us. It must be mentioned here that the people had their own system of farming, used their own seeds, and an irrigation system that did not consume as much water as one needs today for the high yielding crops.

An irrigation system was planned with the extension of canals in the Kamla project, in early 1950s, and the King’s Canals were later merged with this system. A weir was constructed on the Kamla near Jainagar to divert water into the canals and it was anticipated that all the problems related to irrigation would be solved. Unfortunately, this did not happen. The availability of water was uncertain in Kamla canals. The water stagnates on the northern face of the canal thereby damaging the crops therein. A large chunk of land is waterlogged in the Kamla project because of the embankments and the canals.

The first major setback to the Kamla embankments was in 1965 and the state's response was of strengthening the embankments. Seeking flood protection through embankments is like walking into a trap where every action leads to a new and costly measure and the problem goes on deteriorating with time. The decision whether to build embankments or not, however is mostly taken by politicians and, for obvious reasons the engineers are made to defend them. Also, breaches in the embankments continue unabated.

Image courtesy: Dinesh Mishra

The author has tried to trace the river through scriptures, folklores, British raj and independent India. There is a divergent view about the rivers among rulers, administrators, engineers, river watchers and the people living along them and this diversity of views comes very distinctly in case of Kamla. Human interventions have played a terrific role in perception of the river among different sections of the society. No wonder that the river is seen as mother by some and a devastating force by the other.

There is a wide gap between the peoples understanding and aspirations about the river and the interpretation of the same by the establishment. Misplaced planning and false propaganda about the future benefits and selling dreams lead to very high expectations from various projects, which ultimately fizzle out.

Anupam Mishra in the foreword to the book observes that “the attitude of the policy makers towards our rivers is entirely different to the aspirations of the local people. Both the emerging views are like the two banks of the river, which do not meet. The gap between the banks is widening and so is their depth. Keeping site of the divergent views, the author is trying to bridge them.”

kamla_river_and_the_people_on_collision_course_dinesh_mishra_2006.pdf

kamla_river_and_the_people_on_collision_course_dinesh_mishra_2006.pdf