- Topics

- Feature

- Opportunities & Events

- About

- Hindi Portal

- Data

- Topics

- Feature

- Opportunities & Events

- About

- Hindi Portal

- Data

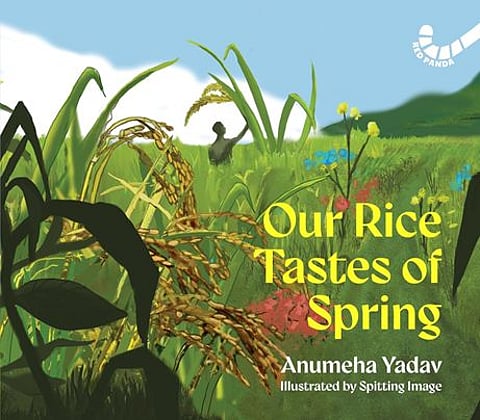

At first glance, Our Rice Tastes of Spring looks like a children’s book, filled with vivid illustrations and lyrical storytelling. But look closer, and it reveals a much deeper tale. Written by Anumeha Yadav and illustrated by the Spitting Image collective, it tells a story about seeds, sovereignty, and survival through the everyday life of a farming family in the Chhota Nagpur region of Jharkhand.

The story follows Jinid and her family, who grow heirloom rice—red, brown, purple, and black varieties that carry memory, culture, and ecology in every grain. When an outsider arrives promising high-yield varieties and prosperity, the family must decide whether to protect their heritage or embrace “progress”. Beneath this simple story lies a larger question India has faced since the Green Revolution: what do we lose when we trade diversity for uniformity?

For children, the book is a sensory feast—immersing them in the colours, smells, and textures of rice, with lush illustrations that linger on the sheen of a grain, the rhythm of a traditional dheki (wooden rice huller), and the play of crabs and fish in flooded paddy fields. It reminds readers that rice is more than food; it is memory, ecology, and community.

For adults, it is a gentle but urgent critique of industrial agriculture, monocropping, and the “technical fixes” that have eroded diversity and farmer autonomy. The narrative echoes Yadav’s reporting on India’s rice fortification policy and its contested implications: the dangers of reducing malnutrition to iron powders and the risks of creating permanent corporate markets at the expense of community food systems.

For communities themselves, it is an affirmation. The book carries village debates, gram sabha discussions, and intergenerational memory back into illustrated form, making it accessible as a resource in meetings and campaigns around seed sovereignty and agroecology.

At a recent book discussion, Yadav situated the project within her decade-long reporting from Jharkhand.

“The book grew from the question: what do village communities remember about their own seeds and farming, and how?”

She began the project in 2022–23 while reporting on India’s policy push for fortified rice as a cure for hunger and anaemia. Her reporting revealed overstated government claims of anaemia reduction, weak testing systems, and communities wary of “plastic-looking” fortified kernels. More importantly, she found that diverse local foods—greens, pulses, forest produce, fish, and landrace rice varieties—already contained natural nutrient richness but were being displaced.

The book thus emerges not just as literature, but as journalism translated into visual storytelling. By embedding reportage into story and illustration, it resists the narrowing of food policy to fortification and reclaims the broader canvas of biodiversity, soil health, water, and farmer autonomy.

“The title Our Rice Tastes of Spring comes from a phrase uttered by farmers,” says Yadav. “Rice is alive with memory and seasonality.”

Unlike hybrid white grains stripped of flavour, heirloom rice varieties are resilient—some withstand floods, others thrive in drought, and some resist salinity. These qualities were not engineered in labs but cultivated over millennia by farmers as custodians of biodiversity and water.

Since the Green Revolution, mixed cropping has narrowed to a few cereals, with heavy fertiliser use, groundwater stress, and rising costs for smallholders. Government research even notes a decline in micronutrients like zinc and iron in rice—soil degradation and water stress showing up in the grain itself.

Yadav makes clear that hunger and anaemia cannot be solved by powders alone. They demand systemic attention—fair procurement for diverse crops, recognition of community seed networks, and policies that value agroecology and local water stewardship. The book does not shy away from showing how corporations and states often decide what farmers grow, cook, and eat.

The Bangalore-based collective, Spitting Image, brings the story alive with an aesthetic that is both playful and grounded. Their illustrations echo oral traditions, scenes of debates around the fire, collective harvesting, and women rhythmically pounding rice. The art avoids romanticising poverty; instead, it celebrates agency, beauty, and continuity in rural life, even as it acknowledges the pressures of markets and state policy.

“We made the book as an illustrated story so it would travel back to villages with dignity and clarity, not just as a dense article,” says Shoumik Biswas of Spitting Image.

Drafts were tested with communities, and details were revised based on their feedback. Hindi and other language translations are underway so the book can be used in meetings and campaigns around seed and food sovereignty.

Our Rice Tastes of Spring is an unusual and necessary book. It shows how children’s literature can be political without being didactic, and how illustrations can carry the weight of journalism. In a time when India’s food policies lean heavily on fortification and uniformity, Yadav’s work is a reminder that true nourishment lies in diversity of seeds, soils, water, diets, and voices.

This is not just a book to read to children. It is a book to discuss in gram sabhas, classrooms, and policy forums. It invites us to remember that rice, like spring, carries the promise of renewal.