The recent World Water Development Report by the United Nations has projected that India's demand for water is likely to surpass availability by 2050. The analysis is based on the fact that the country’s per capita availability of water has declined by three times over the past six decades- the per capita water availability, which was 5000m3 in 1951 has reduced to 1600 m3 in 2011. Given this alarming scenario, the report has also recommended promoting water-efficient technologies in agriculture, domestic and industrial sectors.

While campaigning for the ongoing General Elections, many candidates realizing the priority and importance being given to water, promoted themselves citing big projects such as river interlinking, irrigation, water privatisation and so on but how much of an impact do such cost-intensive projects create, especially since local communities are so far removed from such schemes? Aren't there better ways to battle water scarcity?

There are, and these smaller scale initiatives that local communities have undertaken over many years are the focus of this story. These programmes have created an impact in their immediate environments and have not only benefitted people with surplus water but they have also come without any cost. Cost does not refers to direct financial costs, but the indirect cost associated with bigger projects such as the displacement of people, of using rural water to quench the thirst of urban areas and other such costs, which are largely unknown to the public.

Villagers create water in Himalayas

This is the story of two villages in Uttarkhand that tackled their water woes through patience, wisdom and local water knowledge. One story is set in Ufrenkhal in Pauri Gharwal where villagers transformed a dry ravine into a river and the other story is set in Gauna village in Almorha, which became self-sufficient by harvesting rainwater.

Some 40 years back Ufrenkhal was in a firing range but today this region is covered with lush green forests and has been endowed with the Gad Ganga. The forest and stream is a result of the villagers' efforts for nearly 30 years. With the help of Sacchidanand Bharti, a teacher by profession, villagers dug small percolation pits on slopes and planted grass immediately downhill of the pit to protect its edges. These pits

This system called chal-khal, helped the retained water infiltrate into the soil, replenished the groundwater and created a river. Through this system, once a dry ravine has been transformed into a perennial river that discharges water at the rate of three liters per minute at the source. The method is still practiced in the region and nearly 40 villages have adopted it and have benefitted.

Before 2003, life was a bit tough for people in Guana village, especially for women, who had to walk 3 km down through the steep terrain to fetch water from a spring. Moreover, only three pots of water per household were allowed as the spring was the only source of water for the villagers. However, post 2003 the villagers have started harvesting rainwater and have transformed their lifestyle.

The village is quite steep and therefore, the rain falls and flows towards the plain, making it difficult to replenish the springs. Thus, rainwater harvesting was the most feasible approach for the villagers to adopt. Water is harvested using rooftop rainwater and surface run-off. Through rooftop rainwater harvesting, water is collected in a cemented closed tank, which can be later used for drinking and domestic needs, while the surface run-off is collected via channeling and diverting into the open tanks. This water is primarily used for irrigation and livestock. Today, nearly 155 rainwater harvesting tanks have been installed in Guana and its neighboring villages, where such systems have now now become the norm.

Community revives Sikkim's drying springs

Springs are dying in Sikkim due to environmental and anthropogenic reasons. Owing to the steep topography of the region, 85% of the rainfall goes down the mountains without recharging the spring catchment. But now with the help of Dhara Vikas, an initiative by the state government, communities have constructed trenches with a dimension of 6X3X2 feet at distance of 20 feet uphill and 8-10 feet downhill. Water channels have also been excavated to direct the rain water to these trenches. This arrangement is a way to store the rainwater and replenish the springs without disturbing the source. Now, the region has become self-sufficient in water and Dhara Vikas is continuing its efforts to revive the many dying springs in Sikkim.

Springs are dying in Sikkim due to environmental and anthropogenic reasons. Owing to the steep topography of the region, 85% of the rainfall goes down the mountains without recharging the spring catchment. But now with the help of Dhara Vikas, an initiative by the state government, communities have constructed trenches with a dimension of 6X3X2 feet at distance of 20 feet uphill and 8-10 feet downhill. Water channels have also been excavated to direct the rain water to these trenches. This arrangement is a way to store the rainwater and replenish the springs without disturbing the source. Now, the region has become self-sufficient in water and Dhara Vikas is continuing its efforts to revive the many dying springs in Sikkim.

Revival of the Meghal river in Junagadh, Gujarat

In Junagadh located in Saurashtra, Gujarat, farmers revived the Meghal river with the help of the community, without taking any support from the state government. Once a perennial source of water, the Meghal dried up due to excessive use. The water crisis of the village was further aggravated during the droughts of the 1980s and 1990s that left dry the borewells, tubewells, tanks, handpumps and dipwells in the village. With no scope of agriculture left, farmers started to migrate to cities in search of employment.

To tackle this situation, several villagers joined hands and through community action built check dams to store large quantities of water that could cater to the needs of the village year-round. In addition to this, the farmers have adopted sustainable ways to conserve water by using drip irrigation and sprinklers to irrigate their farms.

Bringing back to life traditional water systems

Magadh Jal Jamaat is a group of progressive citizens, who have successfully revived over a dozen traditional water systems, ahar pyne in Gaya, Bihar. From conduits of wastewater and dumping grounds of solid waste, the ahar pynes have been transformed into their original forms. Pynes are the diversion channels to lead the floodwaters of the rivers into the ahars, a reservoir with embankments on three sides. Likewise, Dilasa, a Yavatmal-based voluntary development organization, has been reviving and promoting the phads or diversion-based irrigation systems in the Vidarbha region of Maharashtra.

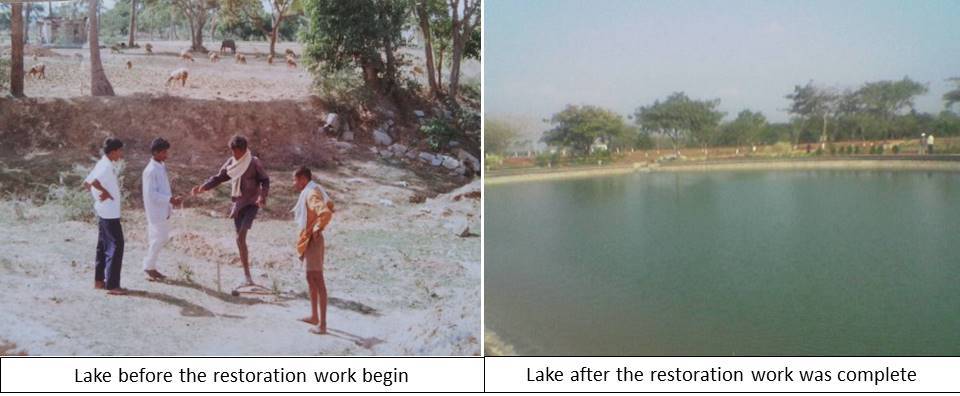

Local community gives a fresh lease of life to lakes

In its search for old and abandoned water bodies in South India, Ecoserve, an environmental company in Bengaluru, found an old lake bed in Guntur, Andhra Pradesh which was 1500 km2 in size with a storage capacity of 25 lakh liters water. The lake was dry for many years and had cracks in its bed, which led to a high percolation loss. Ecoserve decided to treat the lake bed by layering, leveling and compacting the soil. The treatment, which was conducted for almost a year, has shown spectacular results as the percolation rate of the lake has now reduced by 90-95% and rainwater is collected.

In its search for old and abandoned water bodies in South India, Ecoserve, an environmental company in Bengaluru, found an old lake bed in Guntur, Andhra Pradesh which was 1500 km2 in size with a storage capacity of 25 lakh liters water. The lake was dry for many years and had cracks in its bed, which led to a high percolation loss. Ecoserve decided to treat the lake bed by layering, leveling and compacting the soil. The treatment, which was conducted for almost a year, has shown spectacular results as the percolation rate of the lake has now reduced by 90-95% and rainwater is collected.

Now, the lake is no longer dry. The total cost of the project was Rs 15 lakh only, which means that less than a rupee was spent to collect one litre of water. The project was 50% sponsored by corporates, 25% by the government and the remaining 25% by the villagers.

Likewise, Puttenahalli Lake in Bengaluru was revived by a citizens’ initiative. Puttenahalli is a rain-fed lake located in the 7th phase area of South Bengaluru. Looking at the shrinking state of the lake, Usha Rajagopalan launched a campaign ‘Save our Lake’ in 2009 and was joined by three more citizens. Together, they formed ‘Puttenahalli Neighbourhood Lake Improvement Trust’ (PNLIT).

Likewise, Puttenahalli Lake in Bengaluru was revived by a citizens’ initiative. Puttenahalli is a rain-fed lake located in the 7th phase area of South Bengaluru. Looking at the shrinking state of the lake, Usha Rajagopalan launched a campaign ‘Save our Lake’ in 2009 and was joined by three more citizens. Together, they formed ‘Puttenahalli Neighbourhood Lake Improvement Trust’ (PNLIT).

They wrote to the concerned authorities and press regarding the growing encroachments on the lake bed. Bruhat Bangalore Mahanagara Palike (BBMP) finally agreed to their demand of reviving the lake and initiated the restoration work with fencing of the lake as the first step. With residents working closely with BBMP other measures of restoration and beautification of the lake followed. All the expenses of the lake restoration were met by contributions and donations and no local government was approached for funding.

Following the footsteps of PNLIT, another trust has been formed in the city - 'Sarakki Lake Area Improvement Trust' (SLAIT) that has taken the responsibility of securing and restoring the Sarraki lake.

Catching every drop of rain - the ‘Mazhapolima’ way

Nearly 70% of households in Kerala depend on dug wells for their drinking water needs but during peak summers, it is not just the quantity of water but also the quality that affects people. The underground rocks of the region are high in iron due to which the water in the dug wells is hard and it also appears orange in color.

Nearly 70% of households in Kerala depend on dug wells for their drinking water needs but during peak summers, it is not just the quantity of water but also the quality that affects people. The underground rocks of the region are high in iron due to which the water in the dug wells is hard and it also appears orange in color.

In Thrissur, a programme called ‘Mazhapolima’ meaning bounty of rains, was initiated in 2008. Mazhapolima is a type of rooftop rainwater harvesting system, in which the rooftop rainwater is diverted into the dugwells. The implementation of the method has led to an improvement in both the quantity and quality of water.

Now the water in the dugwell is no longer orange. Nearly 65 Gram Panchayats have adopted this method as well. Thrissur has set an example for other districts in the state to follow. Palakkad and Malappuram districts have already begun work to implement Mazhapolima.

Reducing the urban water footprint

It isn't just rural areas that are applying traditional wisdom to tackle their water issues, but also urban folk are adopting ways to reduce their water footprint. People in cities have installed rainwater harvesting systems, recharge wells and greywater recycling systems in their houses. Greywater recycling systems help collect and reuse wastewater from the kitchen, washing and bathing. This can be used for gardening, car washing and flushing. Not just individuals but also apartment complexes in cities are taking such initiatives.

Aabid Surti, a National Award winning author, artist, cartoonist and playwright, uses his Sundays to plug leaks in houses in Mumbai's suburbs for free. Through this approach, has saved more than 1.5 million liters of water from being wasted.

These stories are but a sample of the numerous initiatives that people have undertaken to conserve and harvest water as well as revive water bodies.

Share your water conservation story with us. Remember, no story is too small in the big battle against water scarcity.