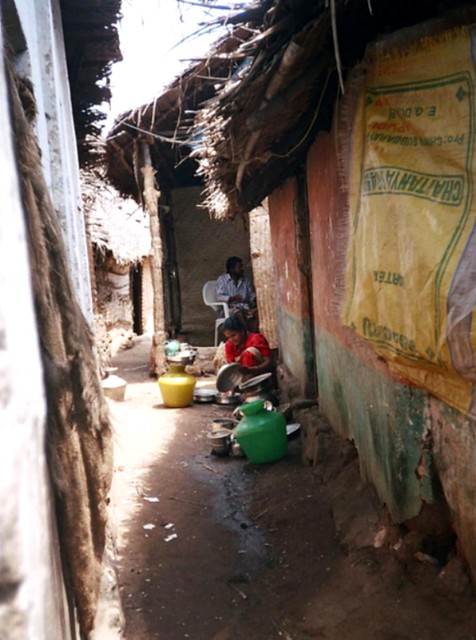

The fisherfolk in Kerala have their own distinctive culture and share a special relationship with the sea and the environment. Although they are an important community in the system, they have remained neglected despite the higher socio-economic progress of the state as a whole. The fishing villages are characterised by high population, poverty and deprivation and lack access to basic services such as water and sanitation. A large number of houses are clustered together and occupy the coastal fringes of the state [1].

The fishing village of Vizhinjham in Thiruvanathapuram district is one of the more important fish landing centres among the 27 fishing villages in the area. Fishing takes place in Vizhinjham all round the year [2]. Currently, plans are being made by the Government of India to convert Vizhinjham harbour into an international port because of its strategic location. The total project expenditure is estimated to be around ![]() 6595 crores and is being planned over three phases. The proposed port is expected to be one of the largest ports in the World [Wikipedia].

6595 crores and is being planned over three phases. The proposed port is expected to be one of the largest ports in the World [Wikipedia].

However, environmental groups, activists, representatives from the fishing communities as well as scientists have warned of the severe negative environmental damage that the port will cause to the region, besides having a negative impact on the livelihoods of a large number of traditional fisherfolk who live in the villages close to the site [ Down To Earth]. Recent news indicates that the government has nevertheless decided to go ahead with the project and the masterplan for the port has now been released [The Hindu]. What impact will this have on the future of the region and the fishing community?

References

1. Asia Development Bank (2003) Regional technical Poverty And Environment Nexus Study. Thiruvananthapuram, Centre for Earth Sciences

2. Vimalakumari, T. K (1991) Chapter 2: profile of the village and community. In: Infant mortlity among the fishermen. New Delhi, Discovery Publishing House. p 19-26.